- Foundation

- Actions

- Osteoarthritis

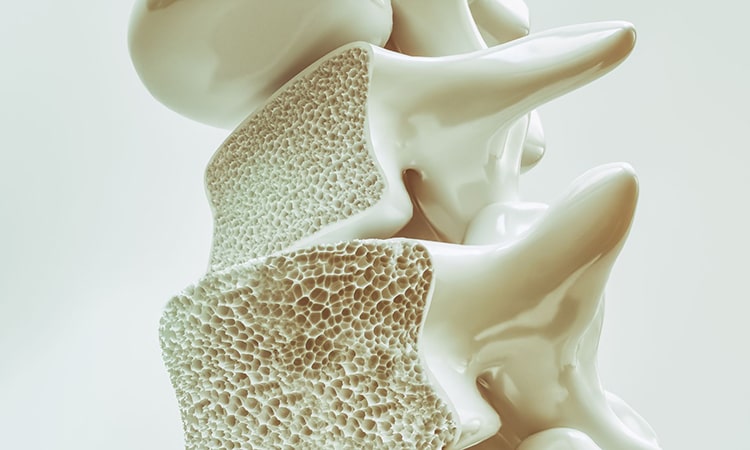

- Osteoporosis

- Actuality

- OAFI Radio/TV

- Get Involved

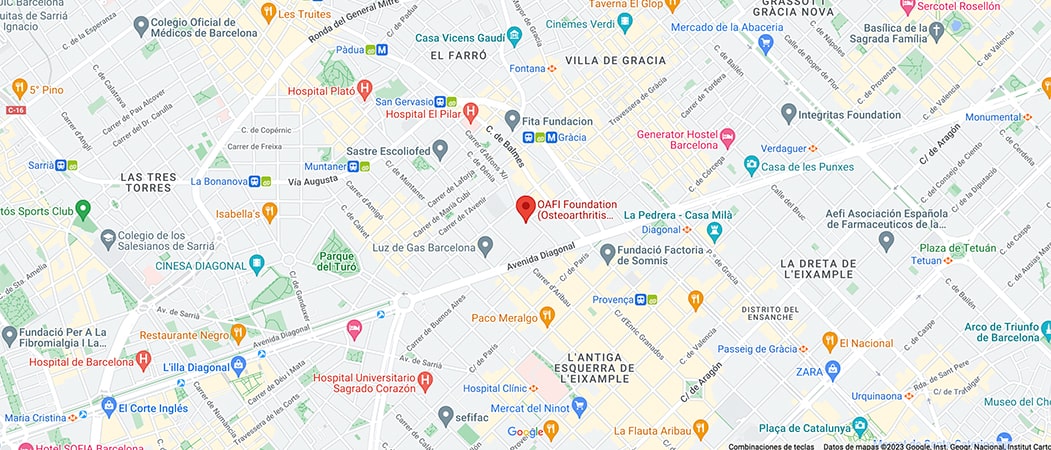

- Contact

-

-

-

OAFI

Osteoarthritis International FoundationC/ Tuset, 19 · 3º 2ª

08006 Barcelona

(+34) 931 594 015

info@oafifoundation.comSchedule:

Monday-Thursday 9AM-6PM

Friday 8AM-3PM

-

-

-

-

-

Beyond the symptom: Understanding chronic pain to get your life back

Prof. Dr. Luis Miguel Torres Morera President of the Sociedad Española Multidisciplinar del Dolor (SEMDOR)

Lm.torres@me.com

To address pain effectively, we must first change our perspective on what exactly we are feeling. It is important to remember something essential: chronic pain is not just a passing symptom or a temporary warning sign.

When pain persists beyond three months, and especially when it begins to affect a person’s functionality and quality of life, it ceases to be a mere warning of tissue damage and becomes a disease in itself. This condition develops its own mechanisms and generates a profound biopsychosocial impact that affects daily life as much or more than the pathology that initially caused it.

This consideration is not an isolated opinion; it is endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and by the international recognition of chronic pain as an independent clinical entity. Understanding this is the cornerstone of a successful approach.

The scenario in Spain: When the body “learns” to hurt

In Spain, the reality of chronic pain is an everyday occurrence for many people. Most of those who live with this condition do so in the context of musculoskeletal, bone, and joint diseases. We are talking about common diagnoses such as osteoarthritis, low back pain, tendinopathies, spinal stenosis, disc pathology, or the lasting effects of surgery.

These conditions are extremely common and are often associated with advancing age, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, or physical strain from work.

However, the problem worsens when these processes are prolonged over time. This is where neurophysiology plays a crucial role: the nervous system becomes sensitized, amplifying the pain signal and keeping it active even when the initial damage is no longer significant or has been resolved.

This phenomenon, known medically as peripheral and central sensitization, is key to understanding why pain persists. It is the reason why some people experience intense pain during everyday activities—such as walking or bending over—that previously posed no problem.

Furthermore, this alteration of the nervous system explains the “multidimensionality” of suffering: chronic pain is often accompanied by sleep disorders, profound fatigue, anxiety, depression, low tolerance for physical exertion, and progressive deterioration of mobility.

Understanding this biological mechanism is the first step toward dispelling one of the most harmful prejudices suffered by patients: chronic pain does not mean that the patient is “exaggerating” or that “there is nothing wrong” simply because imaging tests do not show damage proportional to their suffering. Today we know that pain intensity is not always directly related to the extent of visible structural damage.

Osteoarthritis and the Spine: An Affordable Relationship

Osteoarthritis is a prime example of this complexity. It affects millions of people in Spain, causing stiffness, limited mobility, and persistent pain. It involves cartilage degeneration, low-grade inflammation, and functional deterioration, all of which actively contribute to chronic pain.

The same thing happens in the lumbar or cervical spine. There, the accumulation of small injuries, prolonged poor posture, muscle weakness, and natural aging end up generating a state of constant irritation that the nervous system “learns” to maintain.

It is vital to clarify that this does not mean that “there is no solution.” It means that the simplistic approach no longer works. The solution needs to be more comprehensive.: We must combine medical treatment, intervention when indicated, therapeutic exercise, education in pain neuroscience, and self-care strategies.

5 Common myths that slow down your recovery

There are misconceptions surrounding chronic pain that cause unnecessary distress, delays in diagnosis, and the abandonment of strategies that do work. Debunking these myths is part of the treatment:

- “If it hurts, don’t move the joint.” This is one of the biggest mistakes. Scientific evidence is clear: inactivity worsens chronic pain. Complete rest promotes muscle loss (sarcopenia) and reduces functional capacity, creating a vicious cycle. The key is not to stop, but to seek controlled, progressive, and supervised movement.

- “Pain can only be cured with painkillers.” Painkillers may be necessary to manage crises, but they are not the main long-term solution. Chronic pain requires a multimodal approach: physical therapy, neuromodulation, education, physical activity, interventional techniques, emotional support, and, when appropriate, regenerative treatments.

- “If the MRI shows no serious damage, the pain is psychological.” False. Pain is always real. Neuroscience shows that the nervous system can amplify the pain signal regardless of the radiological image. Although psychology and emotions influence how we perceive that pain, the origin is not “in the head” nor is it invented.

- “Osteoarthritis always progresses and there is nothing you can do about it.” This is false. The progression of the disease varies greatly from person to person. The way you live, move, eat, and treat yourself has a decisive influence. With proper management, symptoms can be slowed, stabilized, and in many cases improved.

- “Interventional treatments are dangerous.” Interventional pain medicine is now a very safe field with a high level of scientific evidence. Techniques such as radiofrequency, neuromodulation, guided injections, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and regenerative therapies are valuable tools. The problem is not the technique itself, but rather using it without a precise indication or without an accredited team.

Your active role: What can you do to improve?

The good news in this complex scenario is that patients play an active and decisive role in their own recovery. They are not passive subjects who simply receive treatment.

These are the six most effective and evidence-based measures for better coping with pain and reducing it:

- Keep moving: Physical activity is the most powerful “medicine” available for chronic pain. It improves mobility, strength, cardiovascular function, and mood, as well as modulating sensitization mechanisms. Each plan should be personalized, but activities such as walking, swimming, gentle strength training, and stability exercises are essential.

- Educate yourself about your illness: Understanding how pain works improves your prognosis. Knowing what to expect, how to interpret your body’s signals, and what decisions to make prevents fear, catastrophizing, and a sedentary lifestyle.

- Taking care of your sleep: Poor sleep dramatically increases sensitivity to pain. Establishing stable routines, avoiding screens before bedtime, and practicing relaxation techniques significantly help to “reset” the nervous system every night.

- Coping with stress: Emotions directly influence pain perception. Tools such as mindfulness, diaphragmatic breathing, psychological support when needed, and engaging in enjoyable activities are an integral part of treatment.

- Control weight and diet: Reducing mechanical stress on joints and decreasing systemic inflammation through diet improves outcomes in both osteoarthritis and spinal disorders.

- Consult with specialists: A multidisciplinary approach—including pain specialists, rehabilitation specialists, orthopedists, neurologists, psychologists, pharmacists, and physical therapists—offers the best chance for functional recovery.

Living with chronic pain is undoubtedly a challenge, but it is not an inevitable fate or a sentence of perpetual suffering. Science has made enormous strides in understanding and treating it. Patients should know that there are options, that chronic pain is a treatable condition, and that regaining quality of life is possible when they act with knowledge, perseverance, and the right professional support.

Bibliography

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom and a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160:19-27.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2-S15.

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279.

- Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain: an archive of systematic reviews. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:2041-2056.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444.

Prof. Dr. Luis Miguel Torres Morera President of the Sociedad Española Multidisciplinar del Dolor (SEMDOR)

Lm.torres@me.com